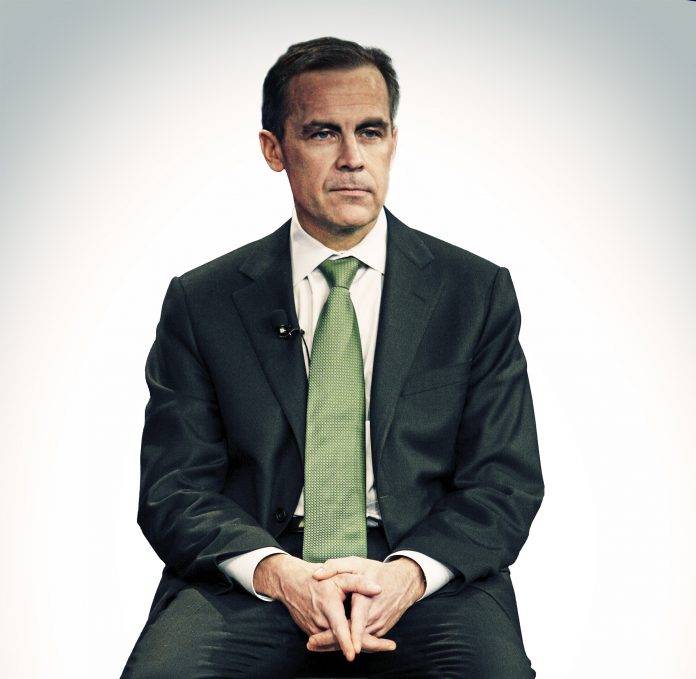

Leading up to the Island Economic Summit 2012,

Douglas caught up with Governor of the Bank of Canada Mark Carney

to talk about our economic outlook, the European crisis, interest rates —

and what he thinks is really needed for full recovery.

He’s been called “the most trusted Canadian.”

The eighth governor of the Bank of Canada has also been tabbed “an insufferable policy wonk” — and maybe the two descriptions necessarily arrive in the same breath.

Mark Carney’s virtue is in his strict attention to the minutiae of macroeconomics and the far-reaching socio-political structures that shape our banking systems at home and around the world. But the 47-year-old’s key ability has been to foster the micro of that macro, advising individuals and businesses on how they can help Canada keep its complex banking and monetary arrangement alchemically golden, through the worst global financial crisis since the Great Depression.

Carney stared down the collapse and kept Canada on a stable footing, averting the devastating impacts that toppled huge banks, rattled markets, and tanked entire economies. Canada actually outperformed its G-7 peers during the crisis.

He’s a man who does it with a curious mix of stern, watchful prudence, casual charm, and a mysterious sex appeal not often bestowed on financiers. He’s got rock star swagger. A movie star smile. And self-confidence some suggest borders on arrogance. When roused, however, the nation’s top banker is more than willing to wield the velvet hammer

of fiscal discipline like some modern, capitalist Thor.

He’s gone further than any Bank of Canada governor has, wading into debates of public policy, hectoring corporations and consumers on debt, dispensing business advice, and sounding the warning that Canada’s debt-fuelled economy is running on fumes.

Carney’s resumé is boldfaced with growing honours. The Canadian Club of Toronto recently named him Canadian of the Year. That came almost on top of Reader’s Digest editors granting him the title of the most trusted Canadian.

Carney’s credentials are blue chip. Schooled at Harvard and

Oxford, he served 13 years as a global investment banker with Goldman Sachs. When he took over from David Dodge at the Bank of Canada, Carney was the youngest central bank governor among the G-8 and G-20 groups of nations. He’s been chair of the G-20’s Swiss-based Financial Stability Board for the past year.

And for added Canadiana, the North West Territories-born, Edmonton-raised Carney was the backup goalie on the Harvard hockey team.

More than half way through an seven-year term with the Bank of Canada, Carney is being courted internationally (although he told BBC during his London visit that he has no plans to become the next governor of the Bank of England) and there are rumours (just rumours, mind you) of his ascension into politics.

Prime Minister Carney, anyone?

Douglas: In advanced economies around the world, there was optimism that 2012 would be a turnaround year. That hasn’t really been the case so far. What needs to happen to bring on a full recovery?

Carney: Prior to the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2007-08, advanced economies steadily increased leverage for decades. That era is now decisively over. As a consequence, the pace of the recovery in these economies is being dampened by the ongoing need by governments, banks, and households to repair balance sheets.

The scale of the challenge is significant.

Across G-7 countries, total debt has doubled since 1980 to 300 per cent of GDP. Global government debt to global GDP is almost at 80 per cent, equivalent to levels that have historically been associated with widespread sovereign defaults.

In the United States, households have experienced a significant loss of net worth: about eight trillion dollars of wealth since the 2007 peak. It will take some time to recover this shortfall.

History tells us that recessions involving financial crises tend to be deeper and have recoveries that take twice as long. The current U.S. recovery is proving no exception. Partly as a consequence, American demand for Canadian exports is $30 billion lower than normal.

Europe’s problems are partly a product of the initial success of the single currency. After its launch, cross-border lending exploded. Easy money fed booms, which flattered government fiscal positions and supported bank balance sheets.

Over time, competitiveness eroded and labour costs in peripheral countries shot up relative to the core. Europe is now stagnating. Its GDP is still more than two per cent below its pre-crisis peak, and private domestic demand sits a stunning six per cent below.

The contraction is driving banking losses and fiscal shortfalls. But these challenges are symptoms of an underlying sickness: a balance-of-payments crisis. That is, countries in the so-called periphery, such as Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Spain, have lost competitiveness relative to other members of the Euro area. This cannot be regained by devaluation within a single currency area. It will have to occur through fiscal and structural reforms, and a sustained process of relative wage adjustment will be necessary. This will neither be easy nor quick, and it implies large declines in living standards in up to one-third of the Euro area.

{advertisement} Douglas: You said in the Financial Times that, “In an unpredictable world, policy makers need a robust framework, one that remains appropriate no matter what the circumstances. Flexible inflation targeting is that framework, a policy for all seasons.” Can you explain flexible inflation targeting and its benefits?

Carney: Since Canada adopted inflation targets in 1991, Canadians have benefited from low, stable, and predictable inflation in a number of important ways: consumers and businesses have enjoyed greater certainty about the future purchasing power of their savings and income; interest rates have been lower; and Canada has experienced more stable economic growth and lower, less-variable unemployment.

The global economic and financial crisis of 2008–09 put the Bank’s inflation targeting regime to an unprecedented test, and it passed. The relative stability of Canada’s economy during that period underscored the benefits of flexible inflation targeting.

There are three key elements to our flexible inflation targeting framework. First, it is symmetric, meaning that the Bank cares just as much about inflation rising above two per cent as we do about it falling below. This helps to foster confidence among Canadians that the Bank will take action as needed to keep inflation low, stable, and predictable.

Second, our monetary policy framework includes a flexible exchange rate that allows the Bank to pursue an independent monetary policy suited to Canada’s needs.

Finally, the inflation-targeting framework is flexible. Flexible inflation targeting provides a goal —

an inflation target — that is both immutable and credible, while allowing for changes in the time horizon over which it is achieved, depending on the circumstances.

Under flexible inflation targeting, a central bank can return inflation to its medium-term target while lessening volatility in other areas that matter for welfare, such as employment and financial stability. Usually, these goals are complementary, and typically the Bank tries to return inflation to target over a horizon of six to eight quarters.

However, sometimes there can be a trade-off between these different objectives. In such cases, the Bank can adjust the length of the horizon over which inflation is returned to target.

When credible, this flexibility allows monetary policy to adapt to changing and complex circumstances in

order to best stabilize the economy. In short, flexible inflation targeting allows central banks to deliver what

is expected while dealing with the unexpected.

Douglas: Canada was the first G-7 country to recover to pre-recession GDP levels, yet interest rates remain historically low. Can you explain the logic behind this trend?

Carney: In the long run, once the effects of all current and past economic headwinds and tailwinds have fully dissipated, inflation can be expected to remain at the two per cent target, economic output can be expected to remain at the economy’s production potential, and the Bank’s policy interest rate can be expected to remain at its long-run level.

Over the shorter run, however, monetary policy can be used to offset the expected ongoing impact of economic headwinds or tailwinds on inflation and output. In these cases, the policy rate will need to deviate from its long-run level to provide the stimulus or restraint necessary to offset these headwinds or tailwinds and return inflation to the target.

The key point here is that, ultimately, the Bank must make a judgment regarding the most appropriate time horizon over which to return inflation to the two per cent target.

Since the crisis erupted four years ago, the Bank has demonstrated its nimbleness in the conduct of monetary policy. We reacted quickly and forcefully during the downturn. As a result, Canada experienced a short, sharp recession.

As the Canadian recovery has progressed, and the economy continued to face external headwinds, we have emphasized that we would be prudent with respect to the possible withdrawal of any degree of monetary stimulus.

In the end, our advice to Canadians has been consistent. We have weathered a severe crisis. Ordinary times will eventually return and, with them, more normal interest rates and costs of borrowing. The Bank of Canada, for its part, will continue to focus on achieving its objective — keeping inflation low, stable, and predictable.

Douglas: The B.C. government has launched a jobs plan called “Canada Starts Here” that focuses on the province’s role as a gateway to trade with Asia and emerging markets, while de-emphasizing commerce with traditional trading partners like the United States. What are your thoughts on these shifting dynamics? From your perspective, is it a good move for B.C.?

Carney: Canada’s poor export performance during the 2008-2009 global recession actually brought into sharper relief some major secular trends that have persisted over the past decade.

Our share of world exports has been declining since the turn of the millennium. In fact, our performance has been the second worst in the G-20.

Broadly speaking, there are three explanations for this deteriorating performance: we may be selling the wrong products; we may be selling to the wrong markets; or we may have become less competitive.

There is some truth in the argument that our poor export performance is the result of competitiveness challenges.

However, competitiveness effects are, in fact, less important than what we call market structure effects. In other words, our export underperformance has been more a reflection of who we traded with than how effectively we did it.

Our exports remain concentrated in slow-growing advanced economies, particularly the United States, rather than fast-growing emerging markets. It does not have to be this way. Many advanced countries have been more successful at capitalizing on the immense opportunity that emerging markets in general and China in particular represent.

And these opportunities are not going away any time soon.

To take advantage, our businesses need to refocus on developing new markets and new products, retool by investing in productivity-enhancing machinery, equipment and IT, and retrain by continuing to invest in our greatest resource — our people.

Douglas: Canada is known as one of the world’s safest, most stable economies — a great place to do business and invest. How difficult has it been to maintain that reputation in the face of the financial upheaval and subsequent challenges of the past four years?

Carney: Canada’s better performance than its G-7 counterparts during and after the crisis can be explained by two factors. First, with a highly credible monetary policy and the strongest fiscal position in the G-7, Canadian policy-makers have been able to respond swiftly and effectively when needed.

Second, Canada’s sound financial system continued to function throughout the crisis. It was not just that no Canadian bank failed or required government capital injections, it was that credit continued to grow throughout the crisis period and into the recovery.

This has given Canada a lot of credibility on the international stage, and in many respects, we have been able to punch above our weight in advocating ways to make the global financial system safer, and the global economy more balanced. Indeed, many of these successful attributes of the Canadian financial system are now being incorporated in other countries.

But now is not the time to rest on our laurels or to take an open global economy for granted. Our ambitions for the Canadian economy should be bold. We are a country of immense strengths and, as demonstrated during the recent crisis, considerable resilience.

We need to continue to make progress on the twin challenges of boosting Canadian productivity and implementing the G-20 framework for strong, sustainable, and balanced growth globally. If we do so, the gains will be considerable.

Douglas: With household debt increasing to record levels and the threat of interest rates increasing, how will businesses be affected?

Carney: Canada’s strong position gives us a window of opportunity to make the adjustments needed to continue to prosper in a deleveraging world. We need to reduce our reliance on debt-fuelled household expenditures, and, in turn, increase business investment. With their balance sheets in strong health, and a financial system that provides ready access to credit, Canadian firms have the means to act — and the incentives.

Canadian firms should recognize four realities: they are not as productive as they could be; they are under-exposed to fast-growing emerging markets; those in the commodity sector can expect relatively elevated prices for some time; and they can all benefit from one of the most resilient financial systems in the world.

The imperative is clear for Canadian companies to invest. This would be good for them and good for Canada. Indeed, it is the only sustainable option available. A virtuous circle of increased investment and increased productivity would increase the debt-carrying capacity of all, through higher wages, greater profits, and higher government revenues. This should be our common focus.

Douglas: What’s the most important thing small business owners don’t know — but should know, to be more successful — about national and global economics?

Carney: Far be it from me to offer specific advice to Canadian business owners. They know their business and their industry best. What we at the Bank try to do is describe some of the broad global trends as we see them, and discuss what the implications of those trends are likely to be for the Canadian economy as a whole.

There are three key forces that are affecting the Canadian economy: the rise of the emerging markets, the outlook for commodity prices, and the great deleveraging that is underway in advanced economies.

The financial crisis has accelerated the shift in the world’s economic centre of gravity. Although this shift to a multi-polar world is fundamentally positive, it is also disruptive. Labour, capital, and commodity markets are changing rapidly.

This has major consequences for Canada and other advanced economies. For example, half of new demand for imports and the bulk of total demand for major commodities now come from emerging markets.

This leads to the second broad force affecting the Canadian economy — the sustained rise in commodity prices. While commodity prices can be expected to be volatile, we expect them to remain elevated compared to historic averages, owing to the strength of emerging market demand.

The third force is deleveraging, a fundamental process at work in the advanced economies. Accumulating the mountain of debt now weighing on advanced economies has been the work of a generation. With the crisis and recession, debt tolerance has decisively turned. As a result of deleveraging, the global economy risks entering a prolonged period of deficient demand.

Canadian firms should recognize these realities, and recognize the clear imperative for them to invest in moving up the value chain, in sourcing new markets, and in improving their competitiveness.

Douglas: Vancouver Island communities have not seen the same level of economic stagnation as some other parts of Canada. What does this region of B.C. do well and, conversely, in what areas can it improve its economic performance?

Carney: Because monetary policy by its nature is national in scope, the Bank of Canada takes a macro view of the Canadian economy, and so we do not publish regional forecasts.

That said, with its reasonably diversified economy, well-educated workforce, relatively wealthy consumer base, a large public sector, and the region’s relative proximity to Asian markets, Vancouver Island has a strong set of economic fundamentals that help explain why it was somewhat insulated from global economic slowdown.

Many industries in this region have made structural changes to improve their competitiveness. At the same time, many new industries and businesses have been attracted to Vancouver Island by its outstanding quality of life and top-quality educational institutions. While there are some structural challenges in historically important resource industries, such as commercial fishing and forestry, the outlook for the region’s mining industry appears bright. Small-scale manufacturing in the region, including the production of niche products and through value-added activities, is another bright spot in the economy. And of course, tourism is already one of the leading industries in the region and has seen significant further development in recent years.

Douglas: You’re in the middle of your seven-year term as governor of the Bank of Canada. What is your assessment of the performance of the Canadian economy over your term, thus far, and what achievements would lead to a successful conclusion to your term?

Carney: I have had the privilege of guiding an exceptional organization through a very difficult time. I have also had the opportunity to travel across the country, meet with Canadians from every province and territory, and have found a quiet pride in how Canada has fared despite the troubles abroad.

The lesson we have all learned over these years has been that it’s important to have a plan, and it’s important to over-perform relative to that plan over time.

Credibility is built with performance as opposed to announcements. I believe the Bank will continue to set such an example in the future, both at home and abroad.

One of my key objectives, given my role at the Financial Stability Board, is that we put in place a series of reforms that build a resilient global financial system. These include ending too big to fail; building resilient financial institutions; creating continuously open markets; moving from shadow banking to market-based finance; and ensuring timely, full, and consistent implementation of all agreed reforms.

This open, resilient, global financial system will be central to the transformation of the global economy

ABOUT

Douglas magazine delivers exciting, in-depth features about Victoria, British Columbia’s vibrant business culture — its startups, disrupters and influencers. With its clear-eyed, contemporary take on business, Douglas inspires local leaders with content about how entrepreneurship is changing our city — and our world.