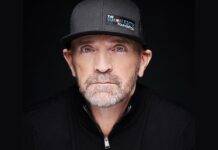

David Curtis’s gamble to take an aging Canadian icon down the runway one more time has Victoria aerospace company Viking Air soaring. Three years ago the CEO and president of Viking went full throttle to put the most famous of the de Havilland Canada (DHC) line back into production, and this re-investment in a fabled brand is paying off.

Flash back 27 years and Curtis, the son of former Saanich mayor and Socred MLA Hugh Curtis, was a Mount Doug grad working in the Queen Charlottes, hopping floatplanes and trying to make his way as a forester. All that puddle jumping on de Havilland Beavers and Twin Otters set him on a different career path and he got his private pilot’s licence in 1983. “I caught the aviation flu,” recalls Curtis.

Around the same time, a mutual friend introduced him to Nils Christensen, who had founded Viking Air in 1970 and was running an aircraft repair operation with a staff of 25. Curtis says it was luck, but Christensen saw an opportunity to take Viking into parts manufacturing and looked to his son and Curtis to take the lead.

“What I learned is that, for anything in the aviation business to work, you’ve got to have your own product,” says Curtis. “You can labour away like a garage, but you’ll only get so big. You need your own proprietary product.”

Three years later, Christensen retired and set Curtis up in an ownership role. Viking prospered, first contracting to manufacturers like Bombardier, Boeing, and Bell Helicopters. Its annual business was between $25 and $30 million. Now it’s about to roll out the first new DHC-6 Twin Otter Series 400. Revenues for 2010 are expected to be $100 million.

An investment in 2003 made Toronto-based investment firm Westerkirk Capital Inc. the major stakeholder and allowed Viking to buy the rights to de Havilland’s well-known aircraft brands. Besides the Otter, Viking is licensed to manufacture six other de Havilland aircraft. Viking’s work force doubled to 450 employees, including 375 in Victoria and the rest in Calgary.

“It afforded us an opportunity to build the company for the long haul rather than with short-term objectives,” says Curtis.

An impressive $15-million, 85,000-square-foot factory and headquarters has replaced the low-ceilinged Second World War-era digs at Victoria International Airport. Viking Air is building an aircraft here that last rolled out of the de Havilland factory in Toronto in 1988.

The reliable Twin Otter made a name in the north and is still used by the military of more than two-dozen nations and 75 airlines around the world. More than 600 of the 844 Twin Otters made by de Havilland are still flying.

Viking’s Twin Otter has new Pratt and Whitney engines, the latest safety systems, and computerized avionics. “Stuff that wasn’t available 25 or 30 years ago,” says Curtis. “We’re not building the airplane that was built 25 years ago. We’re building the plane for the next 25 years.”

How important is it to revive the Twin Otter?

There’s still a market for the airplane. We’ve got 45 orders for new Twin Otters and we’re sold out through the end of 2012. Folks are still using these planes. There are legacy Twin Otters being flown everyday. The DND still uses the Twin Otter.

Who’s buying Twin Otters?

Anyone with search and rescue operations or infrastructure patrols; airlines in Switzerland, Libya, the Maldives, and Russia; the oil and gas sector; the military; locally, Harbour Air.

How much of a sense of nostalgia do you have for the aircraft?

You walk in our building and it starts at the front door. The door handles are shaped like a beaver. We’re like the current stewards of the whole history of this product line. We have a huge responsibility ensuring that the de Havilland and Twin Otter brands aren’t damaged in any way.

Aerospace is driven by low production costs. How do you make things work in Canada?

The bottom line is if you’re trying to grow a business in Victoria where you’re competing on a global scale, there’s always someone who’s going to be cheaper than you. Where’s your edge going to be? What we decided to do is be more product-focused. A Twin Otter is a Twin Otter is a Twin Otter. You can go anywhere in the world and they know what a Twin Otter is. The Twin Otter is a niche player that allows us to be a little more flexible in where we’re based.

Will you continue to manufacture the Twin Otter here and at your plant in Calgary or will you have to move to save money?

The fact is we’ll probably have to do some manufacturing in other countries. It’s quite likely we’ll copy what’s happening in Calgary and do it in India. That’s how we’ll increase our volume.

Is it a case of labour costs alone or the added length of the supply chain to the west coast that will dictate where you build your planes?

There are literally hundreds of suppliers on this program spread across the continent. The tail is manufactured in Fort Erie. The avionics are from Phoenix. And the engines are made in Lethbridge. I don’t want to underestimate the fact that it’s costly to be here. There’s certainly freight and a number of barriers for doing business from here. At the end of the day, you ask yourself, where do you want to work and live and grow your business?

Do we have enough workers skilled in aircraft manufacturing to grow your business?

Certainly when we started out, we thought we had a pretty cool story and we’d attract folks to work here. That was pretty naïve. The cost of living here proved that. One aerospace executive, and I won’t tell you where he was from, told me in 2007 that to move here and replace his five-acre riverfront property and buy something similar here, he’d only be able to afford some kind of townhome and would still have to carry a mortgage.

So we were consistently 30 per cent behind in our hiring.

Are Victoria and the Island proving fertile ground to grow an aviation industry?

What we’re trying to do is help develop more of an aerospace supply chain by getting smaller companies involved in aircraft component manufacturing, like Sealand Aviation out of Campbell River. There’s lots of cross-pollination that goes on all the time. Just down the street, Vancouver Island Helicopters is providing a tremendous amount of work on the wiring of our new airplane. The more local the supply chain is, the easier and cheaper it is to do business.

Does Ottawa help out at all financially?

As far as direct subsidies, no. However, Export Development Canada is invaluable in providing and financing risk performance bonds for customers. It’s really helped us to ensure contracts. The provincial government, on the other hand, has been vaporous.

Transport Canada has a reputation for being strict. Do they make business difficult?

They are the folks who will issue our approval, which we don’t have yet, to deliver an airplane. We’re expecting that in March. It’s easy to bitch about red tape, but I can say beyond a doubt that Transport Canada wants to see this kind of activity in the industry.